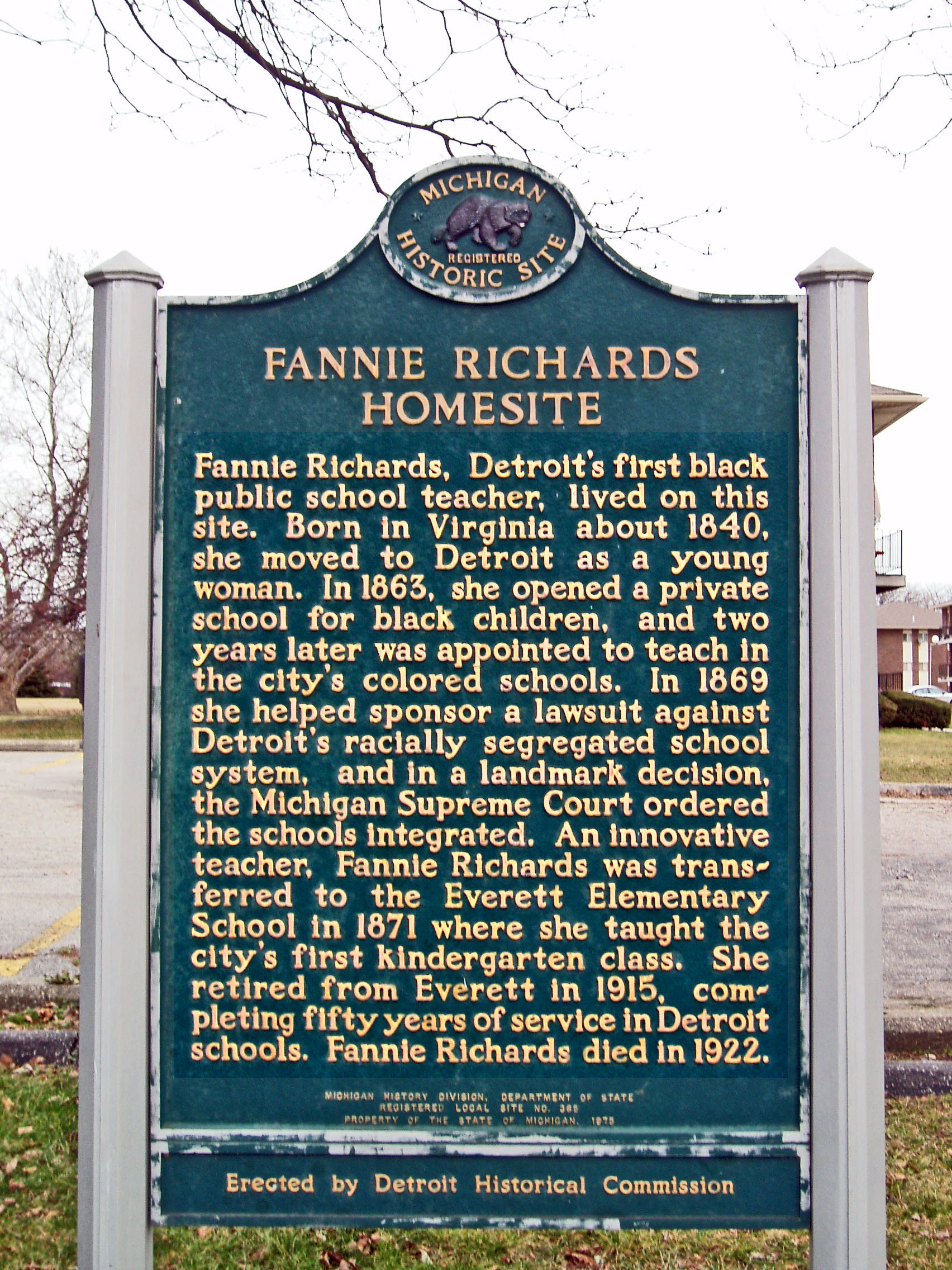

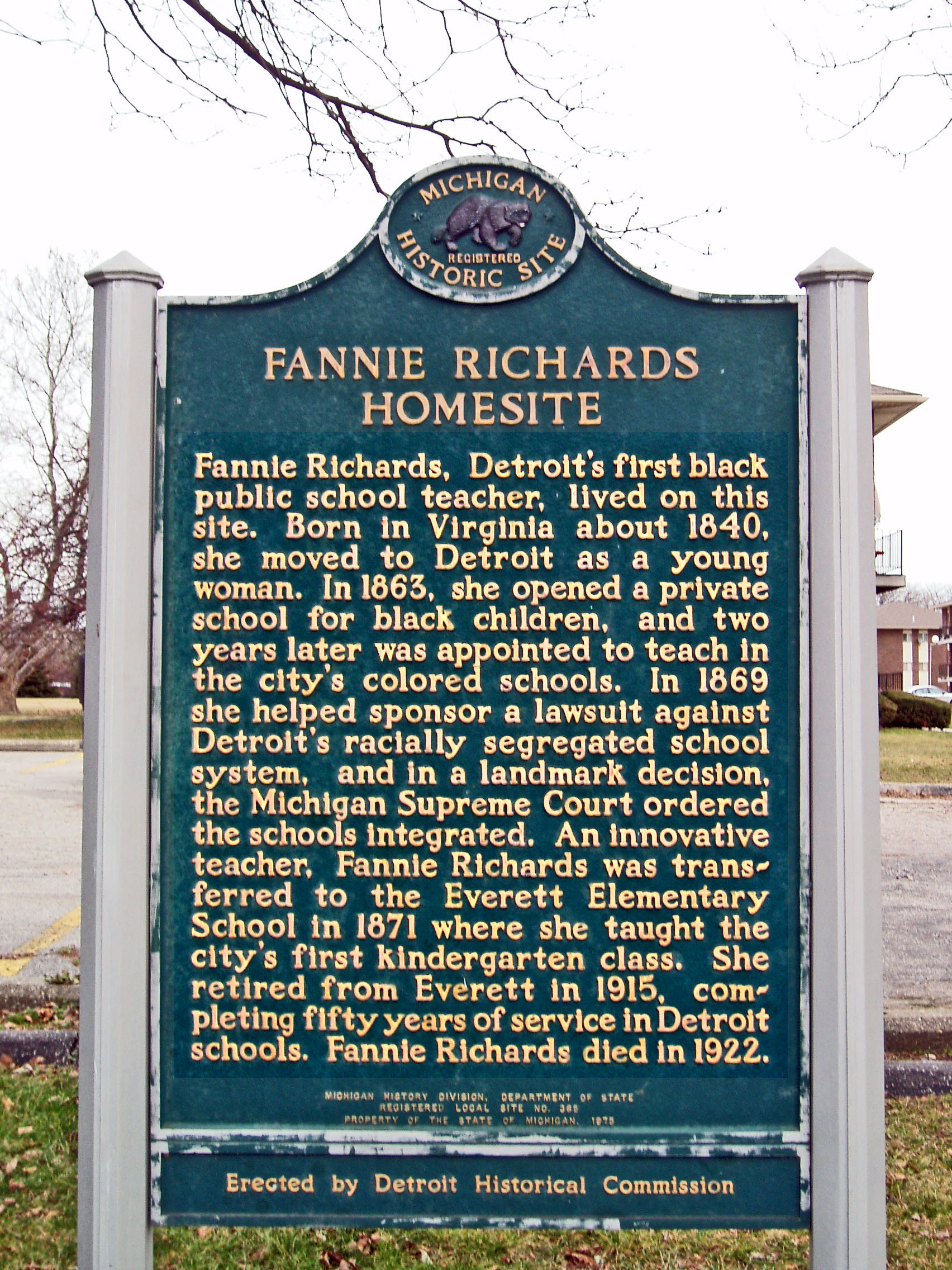

Fannie Richards is commemorated for the important role she played in racially integrating the public schools of Detroit. Richards, an African-American, was born in Fredericksburg, Virginia about 1840. In the 1840s, several cities in Virginia had substantial populations of free blacks. Some of these blacks were quite prosperous, running their own businesses and amassing the resources to purchase spouses or relatives who were enslaved. As the Emancipation movement in the United States became stronger and spread to the heartland of slavery, southern states began to pass laws to restrict their free black populations, such as prohibiting free blacks from teaching slaves to read. They feared that free blacks would propagate ideas about ending slavery to their friends and relatives who were held in bondage. These laws restricting free blacks strongly encouraged those who were able to move to the free states of the North.

Richards moved to Detroit with her family in the 1850s and attended the public schools here. She then went to Toronto to further her education and studied English, history, and drawing. In 1863 she returned to Detroit and opened a school for colored children. Two years later, she accepted an appointment to teach at the one of the two schools the Detroit school board designed for colored children. By the 1860s, that school board had established Jim Crow schools in Wards Four and Seven and, in 1869, intended to open one in the Tenth Ward.

Fannie Richards was one of a number of Detroit leaders who opposed the idea of segregated public schools. In addition, she knew that the schools white children attended had better facilities and offered some advanced grades. The colored schools were at the primary level only and thus were not equal to those attended by white Detroit children.

In April, 1868, Joseph Workman attempted to enroll his mulatto child in the regular school in Detroit’s Tenth Ward. The school board denied his child's admission to the regular school and assigned him to a colored school they intended to open. This set the stage for litigation.

The Supreme Court in Lansing heard the case on May 5, 1869. Workman’s lawyers—H. M. and W. E. Cheever—argued that Michigan law did not permit the segregation of children by race in the public schools, citing a 1867 law that specified that public schools be open to the children of all the rate payers in the school district. Attorneys for the Detroit school board—D. B. and H. M. Duffield—argued that the state gave school district broad latitude to operate public schools as there they saw fit. They argued that was such strong prejudice against colored people in Detroit among the white population of Detroit that it was wise to maintain racially separate schools. Thus, they justified the school board’s decision to assign the mulatto child of plaintiff Workman to the soon-to-be-opened Tenth Ward school for colored children.

Chief Justice Cooley ruled, on May 12, 1869, that the Michigan law of 1867 prohibited all school districts in the state from making any regulation that would exclude any resident of the district from any of its schools because of race, color, religious belief or personal peculiarities. (The People ex rel. Joseph Workman v. The Board of Education of Detroit 18 Mich. 400; 1869). He also noted and emphasized that the schools the Detroit provided for colored children were not equal to those provided to whites. As a result of the Michigan Supreme Court ruling, the Detroit School Board closed its Jim Crow schools at the end of the 1870-71 academic year. It is interesting to note that Michigan’s school integration decision came 85 years before Chief Justice Warren wrote the famous decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

Litigation is generally expensive. While Fannie Richards was active in promoting the integration of Detroit schools, a number of other individuals and organizations provided support, presumably financial support, to hire lawyers. One supporter was John Bagley, the highly successful entrepreneur who served on the Detroit Board of Education and later became Michigan’s Fifteenth Governor in 1873. Second Baptist Church—the older African-American congregation in the city—also provided some of the financial support Joseph Workman needed.

Fannie Richards taught in the Detroit public school system for a half century—from 1865 until 1915. She spent 44 of those years at Everett School. Upon her retirement, she commented upon the many German, Jewish and colored children that she had taught at Everett, suggesting that Detroit public schools once had integrated classes.

Although a great victory for Michigan’s civil rights movement in the post Civil War years, the 1869 decision did not guarantee racially integrated schools in the city of Detroit. The animosity toward blacks that the School Board’s lawyers described in 1869 and demographic trends minimized the racial integration of schools in Detroit.

State of Michigan Registry of Historic Sites: P25,213 Listed November 14, 1974

State of Michigan Historical Marker: Put in place: June

Photograph: Ren Farley

Description prepared: July, 2012

Return to Racial History Sites