At the corner of Michigan and Trumbull southwest of downtown Detroit

Detroit’s first professional baseball team, the Wolverines, began play in the National League in May, 1881 with home games at Recreation Park, a field located where Harper Hospital now stands on John R. For the first few years, the team played poorly. Indeed, their winning percentage was only .250 in the 1884 season. The following year, Frederick Stearns, son of the man who founded the Stearns Pharmaceutical firm whose impressive building stands on East Jefferson near Belle Isle, invested in the team and subsequently became president. Under his direction the team’s performance improved, and in 1887, the Wolverines won the National League pennant and then went on to defeat the St. Louis Browns of the American Association for the national professional baseball championship. Nevertheless, Stearns and the owners of the team apparently lost sizable funds with the team in 1888. At the end of that season, they terminated the franchise, ending the city’s eight-year representation in the National League.

Several unsuccessful minor league teams played in Detroit after the failure of the major league Wolverines. Los Angeles businessman George Arthur Vanderbeck came to Detroit and organized a professional team for the Western Association, a league directed by Ban Johnson and promoted as almost as strong as the National League. Vanderbeck built a small wooden park seating about 3,500 at the corner of East Lafayette and Helen for the team’s first season, 1894. At the time, this area was just beyond city limits. The playing field was known as Boulevard Park or League Park. Vanderbeck imported a number of California players. The next season’s home games were also played at the same park, but then, the nickname was changed from the Detroit Creams to the Detroit Tigers. Vanderbeck apparently told sportwriters that the players he was bringing from California were the cream of the crop, hence the team's moniker.

Small Boulevard Park on East Lafayette was

not a satisfactor y field. At this time, there were two major agricultural

markets in Detroit:

Eastern Market where it still stands at Gratiot and Russell, and

Western Market at Michigan and Trumbull. Western Market was the sales place

for fodder for the city’s horses and also

housed the city’s dog pound In 1895, the city merged the two markets

into Eastern Market and prepared to sell the property at Michigan and Trumbull.

Vanderbeck recognized

that Western Market would be a desirable location for a baseball park so he

purchased or leased it to build a new baseball field. He quickly ran into

opposition from historic preservationists. There were 28 giant old

elm and oak trees on the property; indeed, legend held that Chief Pontiac

conducted a Council of War under one of the massive trees when Indians attempted

to siege the British city of Detroit in 1763. Vanderbeck cut down 23 for his baseball

park but agreed to let 5 trees stand. They only lasted until 1900.

y field. At this time, there were two major agricultural

markets in Detroit:

Eastern Market where it still stands at Gratiot and Russell, and

Western Market at Michigan and Trumbull. Western Market was the sales place

for fodder for the city’s horses and also

housed the city’s dog pound In 1895, the city merged the two markets

into Eastern Market and prepared to sell the property at Michigan and Trumbull.

Vanderbeck recognized

that Western Market would be a desirable location for a baseball park so he

purchased or leased it to build a new baseball field. He quickly ran into

opposition from historic preservationists. There were 28 giant old

elm and oak trees on the property; indeed, legend held that Chief Pontiac

conducted a Council of War under one of the massive trees when Indians attempted

to siege the British city of Detroit in 1763. Vanderbeck cut down 23 for his baseball

park but agreed to let 5 trees stand. They only lasted until 1900.

Vanderbeck rather hastily built a small wooden park seating about 6,000. The new baseball diamond bore the name of Charlie Bennett, the popular catcher on the city’s 1887 championship team. There was great sympathy for him since, during an off-season hunting trip to Kansas, he got off a train at Wellsville. The train began to pull out of the station and Bennett attempted to reboard only to slip toward the wheels. As a result of the accident, he lost his left foot and his right leg was amputated at the knee. He continued his involvement with the Detroit Tigers into the mid-1920s.

Detroit played at Bennett Park in the Western Association through the 1900 season. For the 1901 season, Ban Johnson’s Western Association dropped four franchises in moderate sized cities—Buffalo, Indianapolis, Kansas City and Indianapolis—but added teams in four populous eastern seaboard metropolises: Baltimore, Boston, Philadelphia and Washington. Then he declared the league to be the equal of the well-established National League. Thus Detroit has held a franchise in the American League since its inception in 1901.

Vanderbeck sold the Tigers after the 1899 season. Wayne County

sheriff, James Burns owned the franchise during its first year of operation

but, in 1902,

he sold the team to Samuel Angus. He, in turn, sold the Detroit Tigers in 1904 to

William Yawkey who inherited a fortune from his father, William C. Yawkey,

a highly successful Michigan lumber baron and mining entrepreneur. William

Yawkey step-son, Tom Yawkey, owned the Boston Red Sox for decades. Frank Navin

had worked in the Tiger’s front office for several years and, under WilliamYawkey’s

ownership began to run the team. Apparently William Yawkey was something of

a prosperous dilettante who did not bother himself with the fiscal details

of running a baseball team. Navin not only ran the team but, by 1907 had purchased

controlling interest but Yawkey continued hold some shares until his death

in 1920.

The American League Tigers were financially successful. The Tigers crowds at Bennet Park were

augmented by two important developments. Late in the 1905 season, the Tigers

purchased Ty Cobb from the Augusta minor league team and, within several years,

he helped to boost attendance. Cobb was certainly not personally popular with

other players nor with fans. He was known for his acerbic personality, his

tendency to brutally fight with other players and fans, and his rather frequent

arrests for assault. Indeed, when the Tigers played Pittsburgh in the 1909

World Series, Cobb could not travel through Ohio because of an outstanding

warrant for his arrest for felony assault. Neverteless, Cobb led the Tigers

to the World Series in 1907, 1908 and 1909. In addition to the on-field success

of the team, Navin got Detroit to alter its blue law so that Sunday games could

be played in the city. Season attendance at American League home games at small Bennett Park ranged from

a low of 174,000 in 1906 to a peak of 490,000 in 1909.

After the 1911 season, Navin had Bennett Park torn down and replaced with the park that you see. Work had to be done hastily, and by March of 1912, laborers worked around the clock. On April 20, 1912, the new park opened with a seating capacity of 23,000 but designed for a second deck. Interestingly, this is the very same day that Fenway Park opened in Boston. This original component of the park, including the lower deck stands, extending from home plate down the first and third base lines remained until 2009. The new park—named Navin Field—covered about twice the geographic space of Bennett Park. Home plate was also shifted.

In 1920, the shares that William Yawkey owned were sold to very successful Detroit men who had capitalized on the new vehicle industry, John Kelsey of Kelsey Wheel and Walter O. Briggs of Briggs Body. The influx of their money allowed Navin to add the planned second deck. By 1922, the seating capacity was increased to about 26,000. Subsequent additions during the booming 1920s brought the capacity up to 39,000.

The Detroit Tigers won the American League pennant in 1934, but lost to the St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series. The following year they again won the pennant and defeated the Chicago Cubs for the world championship. Within a few weeks of their victory, Frank Navin died and his wife promptly sold his controlling interest in the team to Walter Briggs, who owned the team until his death in 1952. After purchasing the franchise, he changed the ball park’s name to Briggs stadium. The success of the team on the field in the mid-1930s and the sharp but brief upturn in vehicle sales in late 1936 and 1937, probably played a key role in Briggs decision to expand seating capacity for the 1938 season, primarily by extending the upper deck around much of the outfield. That remodeling gave Detroit the third largest professional baseball park. Only those in Cleveland and the Bronx were larger. This remodeling added the well-known and unique upper deck “porch” in right field.

During Mr. Briggs’ presidency, the Tigers fielded competitive teams

and won the league championship in 1945 and, once again, defeated the Cubs

in the World Series. However, the team was reluctant to rush into innovations.

The Cincinnati Reds began playing major league baseball under lights in 1935.

The Tigers waited 13 years to add lights to Briggs Stadium. Mr. Briggs was

often portrayed by sports writers as strongly opposed to the use of African

Americans players long after Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in

1947. Following his death, local civil rights organizations pressured the team

to integrate and, on June 6, 1958, the Tigers added a dark skinned Puerto Rican

to their roster, Ossie Virgil. Only Tom Yawkey’s Boston Red Sox maintained

the color line longer than did the Tigers.

Mr. Briggs’ son, Spike, became president of the team upon his father’s death but the estate was contested and probate court ordered sale of the team in 1957. The park’s name was changed to Tiger Stadium in 1960. Attendance at the park you see ranged from a low of 204,000 in 1918 when the season was truncated by World War I to 2.7 million in the 1984 World Champion season.

Although this baseball park had great appeal to fans and sports historians, it also had many posts blocking the view of the field and none of the profit-making amenities or luxury suites found in new parks. As early as the mid-1950s, planners and promoters discussed the building of a new park. In the 1960s, city governments in many large towns built new stadia for their professional baseball teams, thereby greatly reducing operating costs for teams. In Detroit, the Red Wings successfully pressured Mayor Coleman Young to have the city pay for a new stadium for his hockey players, but by the time Comerica Park was built, the concept of using city taxpayer’s money to pay for stadia for professional teams was passé. Indeed, Detroit city voters in 1992 enacted a referendum prohibiting the use of local taxes for such stadia. To reduce costs for the Tigers, the city bought Tiger Stadium for $1 in 1978. The city then floated two substantial bond issues—paid for by surcharges on Tiger Stadium tickets—to improve the old ball park.

After years of deliberation and litigation, the Detroit Tigers

amassed the lands, the funds and the governmental approvals needed for the

new park located

in downtown just across Woodward from the Fox and State theaters. While the

team financed the park, infrastructure was paid for by state funds generated

from a new tax on automobile and hotel room r entals in Wayne County.

entals in Wayne County.

On September 30, 1999 the Tigers played their final game in this park, ending a skein of 104 summers when professional baseball was played where Detroit’s Western Market once provided the city’s horses with their feed. The city of Detroit owned the park and paid the Tigers management to maintain the abandoned structure. In 2001, the city sought developers who utilize the site. There were rumors that the site might be used for condos or for a big-box retail store. Baseball aficionados floated plans to retain some of the original 1912 structure for use as baseball park. Others suggested that elements of the 1912 park be incorporated into the architectural design of whatever might be built. But there was no successful redevelopment of the park. The revitalization of the nearby Corktown neighborhood and the transformation of the former Briggs neighborhood into the much more upscale and vibrant Woodbridge Estates neighborhood suggest that the value of the land on which the former Bennett Park stands may be increasingly valuable and appealing to developers. Preservations strongly fought to save at least some section of the park but, in the summer of 2008 when the price of scrap was still high, Mayor Bing approved its destruction.

By November, 2009, all that was left of Tiger Stadium was an empty field of rubble shown to the right.

It is not easy to find clear pictures showing Bennett Park where professional baseball was played from the 1896 through 1911 seasons. I have attached one link below to a Library of Congress photo showing the fifth and final game of the 1907 World Sereies, October 12, when the Cubs - yes, the Cubs - won. Fortunately, the Tigers avenged those World Series defeats in 1935 and again in 1945.There is also a link showing Bennett Park on October 11, 1909 when the Tigers played the Pittsburgh Pirates in the World Series, the third of three consecutive World Series that the Tigers lost.

Architects for the 1912 Navin Field: Osborn Engineering. This

was a Cleveland firm that specialized in building ballparks. They designed Fenway Park and League Park in Cleveland.

General contractor: Hunkin and Conkey of Cleveland

Major subcontractor: Detroit Architectural Work

Electrical contactor: John D. Templeton of Detroit

Picture of Bennett Park, October 12, 1907: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/service/pnp/pan/6a34000/6a34400/6a34430v.jpg

Picture of Bennett Park, October 11, 1909: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/service/pnp/pan/6a29000/6a29700/6a29756v.jpg

City of Detroit Local Historic District: Not listed

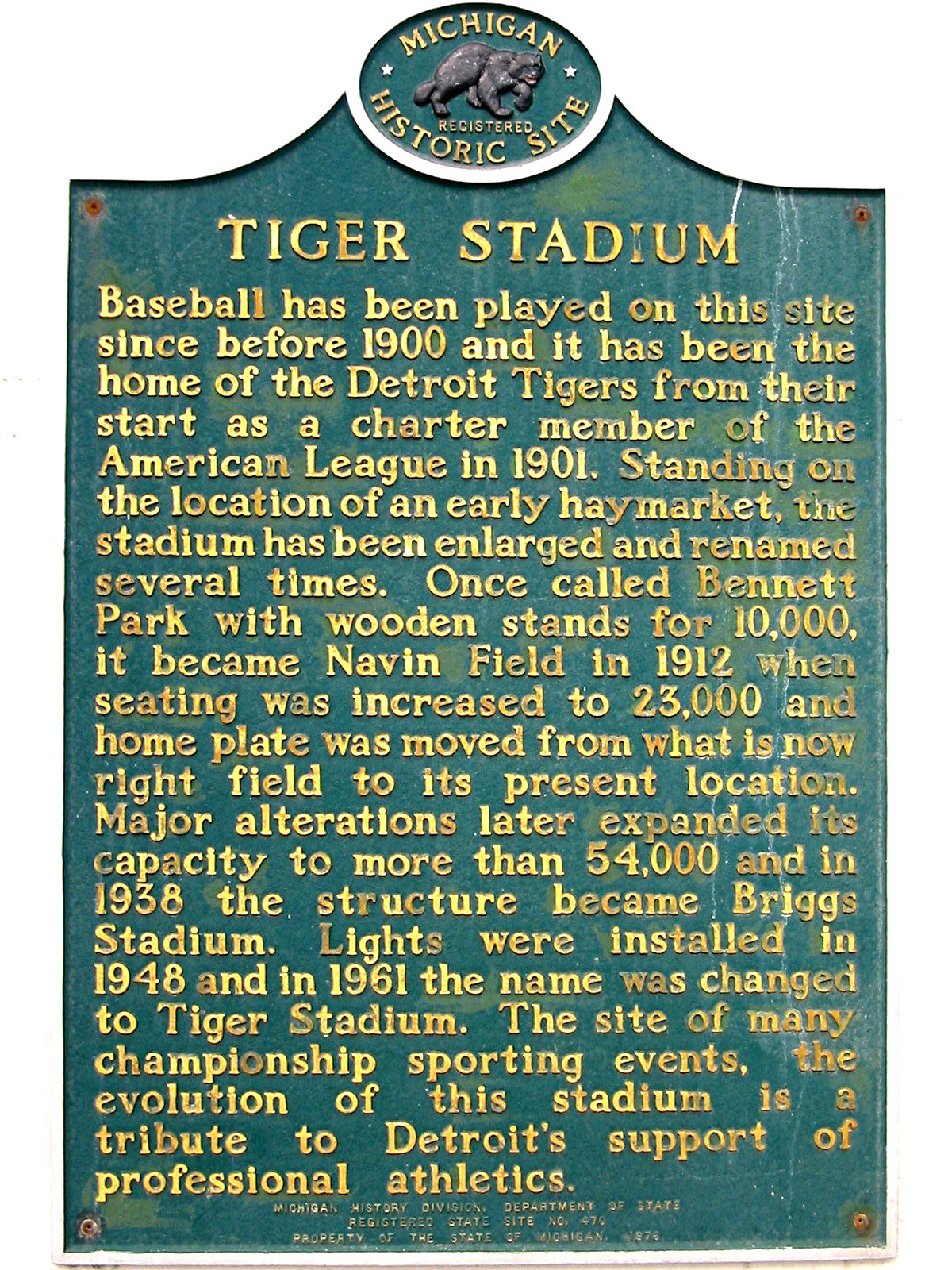

State of Michigan Registry of Historic Sites: P25,188; Listed September 15, 1975

State of Michigan Historical Marker: Put in place June 2, 1976,

National Register of Historic Places: Listed February 6, 1984

Date of demolishment: 2008 and 2009

Picture: Andrew Chandler; July, 2004

Description updated: February, 2011